How to make Iraq's polls a game changer? By giving money!

Corruption is deeply entrenched in Iraq; Barham Salih, the president, recently estimated that $150 billion has escaped the country since 2003 due to embezzlement

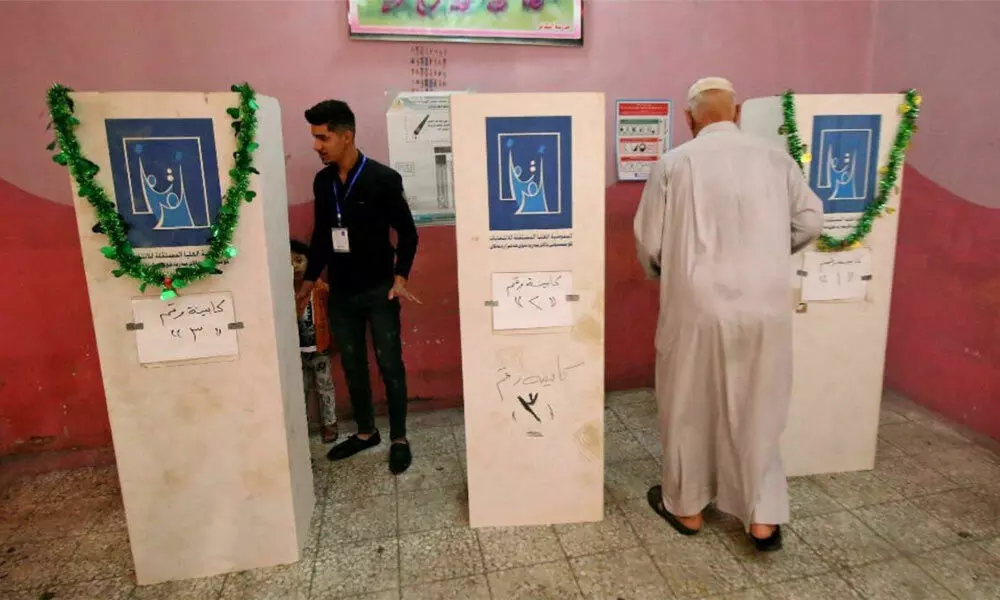

image for illustrative purpose

IRAQ's most popular political TV satire, Albasheer Show, has a fixed segment on corruption called Al-fahagan (the pilfering). It typically features a fraudulent tendering of a contract, a substandard delivery of a project and other forms of swindling committed by politically-connected individuals or parties. It's sad, funny and realistic at once.

Corruption is deeply entrenched in Iraq. Barham Salih, the president, recently estimated that $150 billion has escaped the country since 2003 due to embezzlement — a figure likely to understate the scale of the issue.

The system operates like a pyramid:

♦ At the top is the government, which gets most of its revenue from oil before distributing it to ministries.

♦ Political parties "earn" these ministries (yes, they use this verb) based on the votes they get and the power they wield. They claim government funds and gain influence by awarding contracts and apportioning payroll — appointing supporters and, often, so-called "ghost" or fictitious employees. An official who ran a ministry reckons that these practices ate up half of his budget.

♦ The remainder trickles down to citizens through public-sector jobs, with some (mostly young and marginalised) left out of the system altogether.

The parliamentary elections on October 10 are likely to re-enforce this system of corruption rather than change it. After all, why would the political elite alter a system that's funding them so generously?

One policy can change this and flatten the pyramid: Giving money directly to people through a universal income.

Here's a rough guide on how this could work.

Every Iraqi adult would receive $150 a month into their bank account, irrespective of gender, political connection or employment status. The amount might seem small compared with the average civil servant salary (roughly $800 a month), but this is a stipend for each person not household. A family consisting of two parents and two teenage children would likely receive $600 a month — not a negligible amount.

How will the government fund this? It currently spends about $90 billion a year mostly on public-sector wages. Redirecting half of these funds toward universal income would be enough to finance it. The remainder could be used to retain valuable civil servants in defense, security, healthcare, public administration and other sectors. For the rest of the workforce, the government could offer them a choice between keeping their jobs and receiving the universal income to encourage take-up.

Giving people money directly would reduce the pool of funds available for the discretion of political parties, limiting the scope of their corruption. Why would they agree to it? Well, their approval is useful but not necessary. The source of income is external — money that countries like China and India pay in exchange for oil. The international community can convince these countries and other importers of Iraqi crude to transfer money directly to 25 million accounts (the number of adults in Iraq), bypassing the political elite.

Some might protest that this is an infringement on Iraq's sovereignty. If they do, Iraq can run a referendum asking its population a simple question: "Do you want to receive money directly into your bank account or do you want politicians to be in charge of distribution like the past 18 years?"

A universal income — which doesn't have to be basic, by the way — has other benefit.

It provides a fairer distribution of wealth than the current arrangement. Most of Iraq's recent uprisings, including the Tishreen protests of 2019, demanded jobs for the young and marginalised protestors. They feel the system is rigged in favor of the old and especially the politically-connected. That won't be an issue under universal income — everyone will have equal access to oil wealth. The system would also raise productivity and growth in the private sector by removing the option of government jobs.

Shouldn't Iraq spend its money on improving dated infrastructure and investing in providing public services instead of giving money directly to people? Sure, but that places a bet on the goodwill and efficient management of its political class — a wager that hasn't paid off in the last 18 years and is unlikely to pay dividends in the future.

Wouldn't Iraq struggle to fund universal income if oil prices fall? Yes, but it has also struggled to pay public-sector salaries when petroleum fell in 2014 — it went to the International Monetary Fund, hat in hand, seeking help. In 2020, the downturn in crude was so sharp that it forced the government to devalue the currency to make ends meet.

Universal income reduces corruption, has a better chance of being implemented than other solutions that require the elites to reform themselves against their interests, is fairer and develops a healthier economy. It's not perfect. But it's far superior to the current arrangement and deserves at least to be tested when a new government is formed after the elections. (Bloomberg)